Polio: Types, Causes, & Symptoms

Survivors Of Childhood Polio Do Well Decades Later As They Age

Mayo Clinic researchers have found that years after experiencing childhood polio, most survivors do not experience declines greater than expected in their elderly counterparts, but rather experience only modest increased weakness, which may be commensurate with normal aging."Other researchers have suggested that polio is a more aggressive condition later in life, but we've actually found it to be relatively benign," says Eric Sorenson, M.D., Mayo Clinic neurologist and lead study researcher. "Our results suggest that polio survivors may not age any differently than those in the normal population -- they're not doing too badly compared to their peers. This tells us that the cause for the decline in muscle strength in polio survivors may be aging alone."

Advertisement

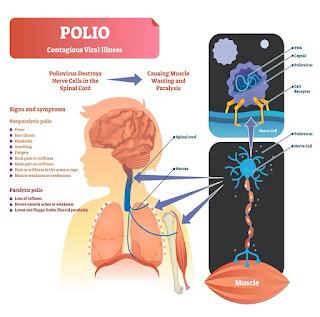

Polio is a contagious, viral illness that peaked in the United States in 1952, when 3,000 people died of the disease. Mass immunizations in the mid-1950s began to slow the spread of the disease, and the last case of polio not caused by a vaccine occurred in the United States in 1979. The three major types of polio include spinal polio, a paralytic polio that attacks nerve cells in the spinal cord; bulbar polio, in which the virus attacks motor neurons in the brainstem; and bulbospinal polio, a combination of spinal and bulbar polios. The effects of polio run the gamut from a complete return to normal function to paralysis of limbs to acute death. Following the illness, most patients are worried about their long-term prognoses, according to Dr. Sorenson.To conduct this study, the researchers randomly selected a group of 50 polio survivors from the general population of Olmsted County, home of Mayo Clinic, and followed them for 15 years. The average age of participants at the study's start was 53, and the patients were an average of 40 years past their childhood experience with polio. The researchers measured strength and loss of neurons at the beginning of this period, and then again five and 15 years later with electrophysiological testing, strength testing and timed tests of performing basic functions. They found modest declines. Each patient also completed questionnaires about symptoms of progressive weakness at the beginning and end of the study period.

Though the majority complained of progressive weakness during the time they were studied, these symptoms did not correspond with their actual magnitudes of decline over time. Rather, the researchers found patients' symptoms experienced were associated with the degree of residual weakness immediately following their polio infections.

"Overall, we found that strength changed very little in these polio survivors as they grew older, and we discovered the neurons dropped off at a rate comparable to other non-polio survivors as they aged," says Dr. Sorenson. "We concluded this was normal aging on top of their old deficits. Very few had to change their homes or add adaptive equipment. Those who had weakness problems during our study had a larger deficit at the end of their childhood disease, making them more likely to develop symptoms. So, as deficits at the end of the disease increase, the probability of experiencing post-polio symptoms increases."

Advertisement

The discrepancy between what some of the patients experienced with growing weakness and their actual measurements of strength and neuronal loss likely is due to increased sensitivity due to their disease experiences, according to Dr. Sorenson."Patients feel their weakness progressing, but when you measure it, it's very modest," he says. "Likely, they lost so much strength at the time of their illness that any change is very noticeable to them. Though the likelihood is high that patients who have had childhood polio will complain of weakness later in life, they can expect years of stability without the need for major lifestyle modifications." (Source: Newswise)

After Long Banning Polio Campaigns, Taliban Declares War On The Disease

December 5, 2023 at 2:00 a.M. EST

A polio vaccinator vaccinates a boy among a group of returnees deported from Pakistan at the Torkham border crossing in eastern Afghanistan on Nov. 11. Two years after their return to power, the Taliban have been actively trying to fight polio, with awareness-raising and immunization campaigns across the country. (Elise Blanchard for The Washington Post)Comment

Add to your saved stories

SaveACHIN, Afghanistan — During its 20-year armed campaign, the Taliban repeatedly banned door-to-door immunization campaigns, helping to make Afghanistan one of only two countries where naturally acquired poliovirus is still endemic.

Two years after the Taliban took power, however, it has done an about-face, and its unexpected efforts may now represent the best shot in two decades at eradicating the highly transmissible, crippling children's disease in Afghanistan.

Vaccinators in the country's northeast, the center of the poliovirus outbreak, search cars for unvaccinated children at roadside checkpoints manned by Taliban soldiers. With no deadly attacks on public health campaigners reported in Afghanistan this year, they also feel increasingly comfortable venturing into remote virus hot spots that were previously far beyond their reach.

"We now have access all over the country," said Hamid Jafari, director of the WHO's regional polio eradication program.

After years of disrupting public health campaigns and amplifying vaccine skepticism, the Taliban now faces challenges of its own making. But the Taliban-run government says it is committed to the effort, and the unlikely alliance between officials and internationally funded health workers — if still at times uneasy — reflects the considerable shift in the priority the government puts on vaccinating Afghans against polio and other infectious diseases.

"It's a priority for us," Zabihullah Mujahid, the Taliban spokesman, who for many years was tasked with announcing the group's bans, said in an interview.

The Taliban's resistance to door-to-door campaigns, he insisted, was never ideological. Much of its opposition arose after the CIA, seeking to hunt down Osama bin Laden, ran a fake hepatitis vaccination program in neighboring Pakistan aimed at collecting DNA that matched that of the al-Qaeda leader. While U.S. Officials say the program never succeeded in collecting DNA from residents of the Abbottabad compound where bin Laden was later killed by U.S. Navy SEALs in 2011, the intelligence effort fostered distrust of vaccinators across the region and exposed them to a wave of deadly attacks after the ploy was revealed.

"We didn't dare to go to villages for funerals of relatives out of fear that we'd be shot there," said Abdul Rahman Ahmadi Shinwari, a vaccinator.

On a recent day, Shinwari was at work at the Afghan border crossing of Torkham, accompanied by Taliban soldiers. "It's a relief to be able to just stand here today with these men," he said.

Changed minds

Qari Najib Ur Rahman, who manages an immunization team in Afghanistan's northeastern district of Achin, said claims by local villagers that vaccines are un-Islamic and Western conspiracies disappeared virtually overnight after the Taliban takeover.

To prove his point, he turned around and pointed to a checkpoint, where two of his vaccinators surrounded cars that had been stopped by armed soldiers next to the Taliban's Islamic Emirate flag. As the vaccinators immunized children inside the vehicles, taking only seconds to pour the vials and mark their hands with a pen, nobody in the packed cars appeared to object.

"Those who had believed that vaccination was forbidden in Islam changed their minds after seeing the Taliban allow it," said Faizullah Shinwari, a vaccination coordinator in Achin. "'If the Taliban approves of it, it must be permissible,' they thought."

Afghanistan bureau chief Rick Noack spoke with the Taliban in Afghanistan on its campaign to eradicate polio, a reversal of its ban on immunization campaigns. (Video: Joe Snell/The Washington Post)

Health workers said the Taliban had never been adamantly opposed to immunization, unlike the Islamic State group, but during the war had more pragmatic concerns that the campaigns were a cover for spying.

Vaccination volunteers in Achin, long a poliovirus hot spot, said the Taliban's endorsement of immunizations has led to a significant overall decline in vaccine holdouts over the past two years, from around 230 cases per campaign to around 60 most recently, even as the number of children reached by vaccinators here has more than doubled.

Public health hurdles

Increasingly, the primary obstacles to vaccination in Afghanistan are practical and not ideological. At Achin's district hospital, 37-year old Tahsildar was late for a vaccination appointment for his 1-year old nephew, who was wrapped in a thick wool hat, and according to Tahsildar, was suffering from a cold that morning that had prevented them from leaving on time.

"Of course, he will get ill if you don't vaccinate him," the doctor scolded Tahsildar.

Visibly embarrassed, Tahsildar revealed the real reason they had missed their appointment. There was no male family member who could have accompanied the child's mother, he said, a requirement that is customary in many rural Afghan areas and emphasized by local Taliban officials. Tahsildar, a farmer, had to skip work for his nephew to be vaccinated.

Meanwhile, it is difficult to reach rural Afghan women with public health education because they are largely isolated in their homes, so it is harder to convince them of the benefits of immunization, vaccinators said.

And some villagers who are vaccine skeptics are demanding to be rewarded for getting immunized.

"Previously, people used to tell us that vaccines are Western people's urine," said Shahidullah Shinwari, a vaccination coordinator in Achin, who is tasked with convincing holdouts. "Today, those who reject the vaccines want financial aid and assistance in return," he said.

Vaccinators and other public health campaigners say there are no penalties for refusing vaccines. But in Achin, parents who refuse to have their children immunized may these days find themselves summoned to the local Taliban district governor's office, where balaclava-wearing armed soldiers line the entrance.

Pakistani peril

At least six polio cases were reported in Afghanistan this year, up from two last year, with a potentially much higher number of unknown infections. From northeastern Afghanistan, the virus is also believed to have spread via refugees and cross-border travelers to communities in Pakistan, where the virus is also endemic.

While Pakistan has made significant progress in fighting the virus over the past year, health officials worry that it could again start spreading more widely in Afghan refugee communities and, amid an ongoing Pakistani campaign to deport 1.7 million of them, make its way into new parts of Afghanistan, too. Refugees who were returning accounted for around half of the people who have in recent weeks rejected polio vaccines in Achin, said campaigners there.

Many lived in Pakistani camps or neighborhoods where conspiracy theories continue to be propagated largely unchallenged.

Pakistani militants who have sworn allegiance to the Afghan Taliban continue to disrupt vaccinations as part of an expanding insurgency, threatening public health progress on both sides of the border.

Unlike the Afghan Taliban, the Pakistani Taliban, also known as Tehrik-e-Taliban Pakistan, or TTP, has shown no hesitation in claiming responsibility for attacks targeting vaccination efforts over the past decade. The TTP still views police officers or soldiers who guard vaccinators as legitimate targets, said a TTP commander, speaking on the condition of anonymity because he was not authorized to speak to journalists. Suspected TTP militants on Friday killed a Pakistani police officer guarding vaccinators in the northwest of the country.

The Pakistani government has urged the Taliban-run Afghan government to rein in the TTP, which Pakistan alleges is operating from safe havens inside Afghanistan. Afghan officials reject the Pakistani accusations.

In Pakistan, many vaccinators say their jobs are today as dangerous as they once were for their Afghan counterparts. In a predominantly Afghan neighborhood on the outskirts of Islamabad, vaccinator Kinza Khan, 23, said she at times only feels safe when accompanied by her husband. "There is always a chance of sudden clashes, of rage," she said. "Some believe it's a foreign conspiracy to make our children infertile."

Nadeem Jan, Pakistan's caretaker health minister, acknowledged that the country faces an uphill battle as it seeks to confront "small" but concerning anti-vaccine pockets of the population. "We're struggling with convincing them, with winning their hearts and minds," he said, citing poor motivation among underpaid vaccinators as one key obstacle.

Pakistani officials may hope that their planned expulsion of Afghans may shift some of the burden onto Afghanistan. But among those who stay, rising distrust of the government could deepen misconceptions.

"The virus takes Pakistan and Afghanistan as one country," said Shahzad Baig, who oversees Pakistan's polio program. "As long as we don't eradicate the virus from the other side, it will keep on coming back and forth."

Lutfullah Qasimyar in Torkham, Afghanistan, Haq Nawaz Khan in Peshawar, Pakistan, and Shaiq Hussain in Islamabad contributed to this report.

3 Issues To Watch In Global Health In 2024

As we enter the fifth year of this challenging decade, life finally appears to be inching toward normal — a new normal — on the infectious diseases front.

Humans and the SARS-CoV-2 virus seem to be making progress toward a detente with each other. Covid is still a major disruptor, a significant cause of illness and death. But the massive disease waves of the early 2020s have calmed down. Masks, in the main, have disappeared. Holiday parties are back. Covid is falling out of the headlines.

But in the world of infectious diseases and global health, if it's not one thing, it's another. As we look to 2024, we can rest assured other issues will demand our attention. There surely will be stories that we cannot foresee — no one had global spread of mpox on their 2022 predictions list, for instance. But here are three health issues we're pretty certain will bear paying attention to in the year ahead.

Will 2024 be the year the world finally stops polio transmission?Most years since STAT launched in 2015 we've written a "3 to Watch" article predicting what's to come in the infectious diseases and global health space. Nearly all of them have featured a "Will we? Won't we?" section on polio eradication.

The job of wiping out paralyzing polioviruses, begun in 1988, was meant to be completed at the turn of the millennium. Several subsequent deadlines were set, including the latest, to stop circulation of all polioviruses by the end of 2023. They've all been missed and the 2023 deadline will be too.

But the Global Polio Eradication Initiative, a coalition of six organizations that lead the fight, now insists that 2024 will be the year transmission stops, and that the formal declaration that polio has been eradicated can be made in 2026, after two years without detected cases.

The numbers globally are low, but the challenges are mighty. Yes, there have only been 12 cases of wild polio reported in 2023. (That's not the lowest number ever; there were a mere six cases in 2021.) Yes, two of the three types of wild polioviruses have already been eradicated, leaving only type 1 viruses circulating. Yes, wild polioviruses were reported in 2023 by only two countries. But those two countries are Afghanistan and Pakistan, where vaccinating all children has been a persistent challenge because of vaccine resistance and security concerns.

And then there's the issue of vaccine-derived viruses, known in the polio world as VDPVs. Live, weakened viruses contained in vaccines used in some parts of the world — not the United States — can regain the power to paralyze if they have a chance to spread from child to child. In 2023, at least 411 children in 18 countries were paralyzed by vaccine viruses. That's an improvement over 2022, when nearly 900 children in roughly two dozen countries were paralyzed by vaccine viruses. But getting to zero before the end of 2024 will be a daunting task.

And it will require substantial good luck, not something the polio program has ever had much of. An expert report assessing the status of the eradication effort that was released in the fall warned that the heavy focus on trying to stop spread of type 2 vaccine viruses in Africa was leading to under-vaccination of children against type 1 viruses, creating the possibility type 1 vaccine viruses could take off there.

We hope our "3 to Watch" report for 2025 notes that the clock has started to count down toward an eradication declaration in 2026. But with polio, you can take nothing for granted.

Whither pandemic preparedness and global health cooperation?The World Health Organization has been hosting multinational negotiations on the creation of a pandemic treaty or accord aimed at helping the world respond better the next time a pandemic occurs. The goal is to agree to the wording of the treaty in time for the May 2024 meeting of the World Health Assembly, the annual meeting of the WHO's governing body.

The purpose of the negotiations is to ensure a more equitable global response in the next pandemic, one that doesn't see low- and middle-income countries forced to wait to get access to vaccines, drugs, and essential medical therapies when global supplies are tight. That's a laudable goal, but one that will be very hard to deliver on.

Affluent countries that bought their way to the front of distribution lines during the Covid pandemic are not likely to sign agreements that hamstring them next time. Likewise countries with strong pharmaceutical industries are unlikely to agree to provisions that challenge the ability of those companies to hold intellectual property rights over vaccines and drugs.

Even if language that satisfies a majority of parties can be agreed to, it's not clear if a country like the United States could sign on in the current political context, in which the Republicans hold the majority in the House of Representatives and the Democrats' majority in the Senate is razor thin. Even though such an accord would not require countries to cede national authority and follow diktats of the WHO in a health emergency, it is already being framed as such in some quarters.

Hanging over all of this, of course, is the fact that 2024 is an election year in the U.S., one in which it remains quite conceivable that Donald Trump will win a second term. Trump signaled his intention to withdraw the United States from the WHO in the spring of 2020. His loss to Joe Biden later that year prevented him from formalizing the U.S. Withdrawal. But there's no reason to believe the heavy favorite for the Republican nomination has changed his views on the value of American involvement in international organizations like the WHO, leaving serious concerns about how lasting any U.S. Commitment to a pandemic accord — if one is successfully negotiated — might be.

The impact of climate change on infectious diseasesAs concern about Covid-19 began to wane, the media and at least some portion of the public reset their worry-o-meters to focus on climate change. With good reason — 2023 was declared the hottest year on record and climate disasters abound around the globe.

There are myriad health implications of a warming planet, but the one we're thinking about here relates to the vector-borne infectious diseases — pathogens spread to people from insects like mosquitoes or ticks. "Our warming planet is expanding the range of mosquitoes, which carry dangerous pathogens like dengue, chikungunya, Zika and yellow fever into places that have never dealt with them before," WHO Director General Tedros Adhanom Ghebreyesus warned during a press conference in the lead-up to COP28, the United Nations' Climate Change Conference in Dubai that ran from Nov. 30 to Dec. 12.

Europe has already seen domestically acquired cases of dengue, in Italy, Spain, and even in the Paris region of France. In the United States so far in 2023, there have been 924 cases of domestically acquired dengue — though most (768) were recorded in Puerto Rico. California recorded two locally acquired dengue infections and Texas recorded one. The bulk of the mainland U.S. Cases — 153 — occurred in Florida.

Assessing the risk posed by the climate-influenced expansion of range of the bugs that carry diseases — and therefore the diseases themselves — is a science that's still evolving. (Read this terrific story in Science to get a sense of the current thinking.) But reports of locally acquired malaria cases in Florida, Texas, Arkansas, and Maryland — Maryland? — give people pause.

Watch this space.

Comments

Post a Comment